Faith, the Fracture, and the Fear

A Conversation Between What I Believed and What I’m Becoming

A deeply personal reflection on faith, doubt, and the search for meaning. From the rituals of childhood belief to the wrestling grounds of theology and philosophy, this is a story of breaking, questioning, and staying- of learning that sometimes belief begins where certainty ends.

Faith, the Fracture,

and the Fear!

Early Faith

Faith. Such an interesting concept, foundational to the moral and social structures that shape our world, yet endlessly confusing when examined closely. For a long time, I wrote about faith as though it were universal, as though my faith was the only one that held true, the one everyone should understand by default. I assumed that when I said “faith,” everyone knew I meant my faith, the Christian faith.

That assumption wasn’t malicious; it was inherited. I grew up in a world where truth was singular, not plural. God was real, Jesus was the Son of God, and the Bible was His Word. To question those truths was to step outside the safety of belonging.

I was raised Catholic, a world of incense, order, and quiet reverence. The rhythm of the Mass gave life a kind of certainty: stand, kneel, recite, respond. Later, I found myself in the Pentecostal world alive with energy, music, and miracles. Faith here wasn’t quiet; it was expressive and emotional. If Catholicism had been about structure, Pentecostalism was about fire.

Yet, amid the clapping and the hallelujahs, I began to feel an unshakable discomfort. It wasn’t rebellion or cynicism, just an odd, sudden awareness that something in me had shifted. I no longer felt at home in the certainty that once anchored me. I wanted to love God, not fear Him, but so much of what I’d been taught revolved around sin, punishment, and earning grace.

For the longest time, my relationship with God was shaped by lack, a theology of survival. I prayed not because I was overflowing with gratitude but because I needed something: provision, healing, a way out. I now see how poverty can shape your understanding of faith, how religion, for many of us, becomes less about worship and more about relief. Faith promises a better world when the one you live in feels unbearable.

The Pursuit: Reading My Way Toward God

When I decided I wanted to know God for myself, I went back to the beginning — Genesis. Chapter by chapter, I read with the curiosity of both a believer and a scientist.

But that dual lens soon became a battlefield. The more I read, the more questions arose. Was Genesis meant as a historical account or a poetic metaphor? My scientific training told me to test and verify, to trust evidence and reason. In my career, I trust gravity, magnetism, and light, invisible forces proven through pattern and law. But in church, I was told to accept by faith that the world was made in six days and that the earth was roughly six thousand years old.

It felt dissonant to live in both worlds, one where I measured and calculated truth, and another where I was told not to question it. I realized how easily I dismissed science when it clashed with scripture. I would laugh at evolution, calling it “funny science,” while defending miracles that defied every law of nature I otherwise upheld. It was selective skepticism, and I started to see it.

That realization didn’t make me lose faith; it made me hungry for understanding. I started listening to theologians, philosophers, and scientists, each trying to make sense of the divine from their own corner of the universe. I heard physicists speak about the fine-tuning of the cosmos, how the smallest variation in gravitational constants or atomic structures would make life impossible. “Surely that can’t be random,” some said. “It must be design.”

Others argued that time itself is a human construct, that what we call a “day” in Genesis could have stretched over millions of years for a timeless God. And there were those who proposed that evolution might be God’s method of creation, that divinity and natural process aren’t opposites but partners.

It was fascinating. But also deeply destabilizing.

The Catalyst: Wrestling With God

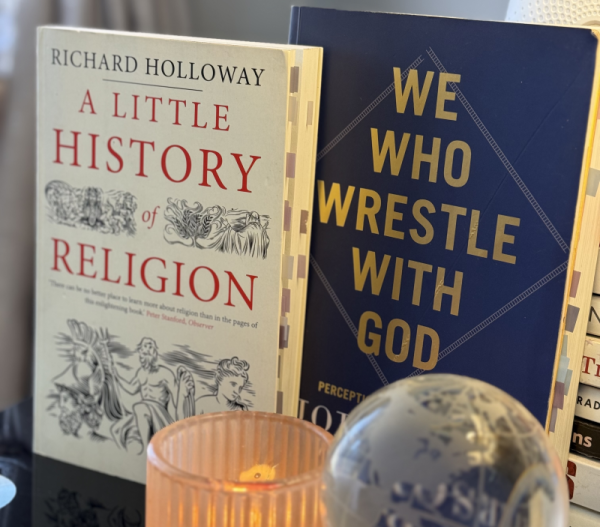

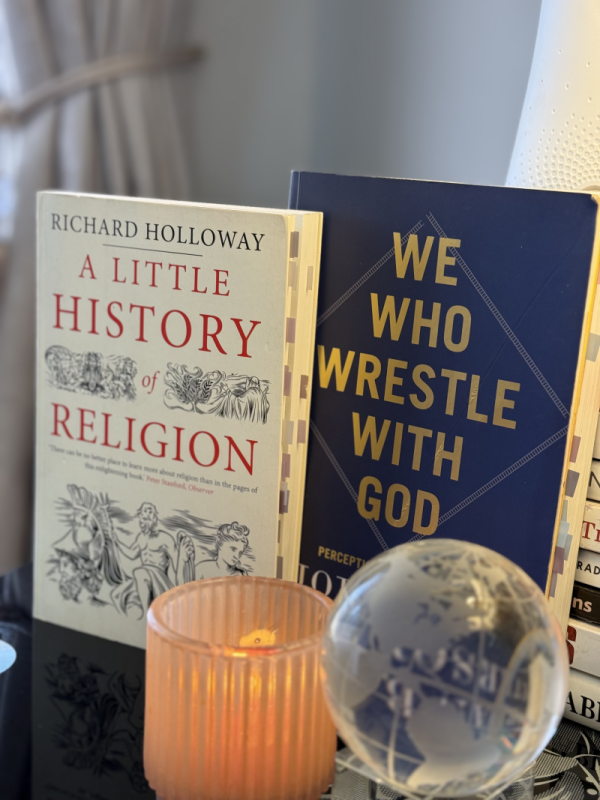

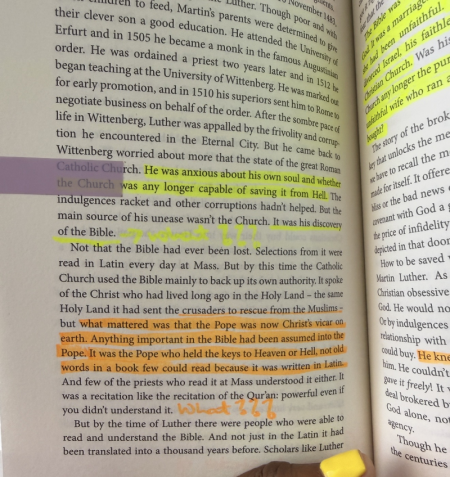

Then I came across Jordan Peterson and his latest work, “We Who Wrestle with God.” The very title felt like a mirror. The first chapter changed everything. Never before had I heard of primordial chaos, the ancient waters of Genesis not as mere backdrop but as symbolism, as metaphor for the struggle between order and disorder, creation and destruction.

Suddenly, the Bible opened up in ways I’d never imagined. The text I had read literally now unfolded as layers of meaning, mythic, psychological, archetypal. I realized people had spent lifetimes wrestling with these same questions, theologians, philosophers, scientists, skeptics, mystics. For the first time, I didn’t feel alone.

I wasn’t as brilliant as most of them, but I belonged to this quiet fraternity of seekers, those unafraid to look into the abyss of not knowing and still search for meaning there. That realization comforted me more than any sermon had in years.

Nietzsche once warned that “if you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.” For a long time, I feared that was my fate, that if I kept questioning, if I kept wrestling with meaning and doubt, I’d become hollow myself. I worried that in trying to understand the darkness, I would become it.

“That faith would collapse into cynicism and reverence into despair or worse, nihilism.“

But as I listened to thinkers like Peterson, I began to see another possibility, that maybe, as he says, the point of descending into chaos is not to stay there, but to wrestle with it long enough to find order, to bring something of light back out. Maybe the abyss doesn’t exist to swallow us, but to shape us, to burn away the naïve faith we inherited so we can rebuild a truer one, forged in honesty.

And perhaps that’s what’s happening to me. I entered this darkness thinking I might lose God, but I suspect I’m only learning to see Him differently, not as certainty, but as the quiet light that follows the descent.

The Fracture: When Knowing Broke the Faith

The more I learned, the less I understood. Each new insight into theology or philosophy revealed just how fragile my old certainty had been, not wrong, just untested. What I had once held as divine truth began to feel more like an inheritance, passed down without question. My faith had been comfortable, but not examined; strong, but not stretched.

“I had always been a biblical literalist. It is, just as it is written. The Bible was inspired by God, not to be questioned, only obeyed.”

And yet, as I wrestled with those questions, something unexpected happened, Genesis began to draw me in again. I started to see it not as history, but as theology; not as fact, but as revelation. It was less about how the world began, and more about why. Jordan Peterson’s interpretation, that Genesis speaks symbolically about chaos, order, and the birth of consciousness intrigued me. It was strange to find beauty in what once felt like a contradiction, and I began to wonder whether the language of scripture had always been poetry trying to explain truth and human curiosity that facts alone could not hold.

But that realization loosened more than it steadied. If the foundation itself could speak in metaphors, what even is religion? Is it divine revelation or humanity’s oldest attempt to name the unknown? From there, the questions led me to the one I had avoided the most, the problem of suffering.

If God is good and all-powerful, why does He allow the innocent to ache? Theologians called it theodicy and offered free will, soul-making, and divine mystery as answers, elegant, but fragile when placed beside reality.

Job’s story lingered in my mind. He was restored, but never answered. God gave him presence, not logic. And perhaps that is what faith demands, to stand before silence and still call it love.

“But I struggled to accept it.”

The Human Pattern: Faith as a Response to Pain

Reading Richard Holloway’s A Little History of Religion brought another uncomfortable revelation. Maybe religion itself is our collective response to suffering, our way of creating meaning when life feels unbearable.

“Every civilization has built gods, temples, and rituals not just to worship but to cope.”

Whether it’s the promise of heaven, reincarnation, or cosmic justice, belief systems give shape to our pain. They tell us suffering isn’t meaningless; it’s part of a larger story.

It occurred to me that both belief and disbelief can spring from the same place. Some people cling to God precisely because of pain, they need the hope that it will end. Others reject Him because of pain, they can’t reconcile a loving deity with such cruelty. Both are trying to make sense of the same wound. This realization didn’t destroy my faith, but it did change how I viewed it. I began to see religion not only as revelation but also as reflection, a mirror of our deepest fears, hopes, and needs.

The Silence: When Doubt Becomes Loneliness

These days, I often find myself surrounded by people of faith who speak as though nothing has changed — friends who make biblical references in conversation, assuming we are in agreement. I don’t have the heart to correct them. How do you say I don’t know anymore to people who still pray the way you once did together? I used to pray for their faith, asking God to strengthen them. Now I wonder, was I wrong to pray for something I no longer possess in the same way?

I’ve always been curious, maybe too much so. My questions have often been called “radical” or “unnecessary.” I’ve been dismissed as the one who overthinks everything. But what do you do when your overthinking becomes your only honest way to live?

Lately, my thoughts keep circling back to Job. We praise him for his endurance, for not cursing God, but rarely do we linger on the silence that followed. He never got an answer. The book ends with restoration, not resolution. His pain wasn’t explained, it was simply overshadowed by God’s grandeur, as if presence were meant to replace understanding.

If suffering is inherent to the human condition, then what is its purpose? Why does it demand attention so loudly, unlike breathing or blinking? Pain seems to be the one constant that refuses to be ignored. Maybe it’s the signal of our need for meaning, the way life forces us to face questions we’d rather avoid. Pain drags us into awareness, into humility, into searching.

The Staying: Faith Beyond Understanding

I didn’t set out to study theology or philosophy. I stumbled into it, chasing clarity and finding only complexity. I used to read my Bible daily; now I can go weeks without opening it. That absence feels both heavy and honest. Still, I can’t fully let go. There are moments: quiet, unprovable moments that make me believe there’s more: a peace that descends in chaos, a coincidence too perfect to be random, a whisper in silence that feels like love.

“So, I stay. Not because I understand, but because I remember. Because somewhere along the way, something real touched me. “

Maybe faith isn’t a destination at all, but an orbit, circling mystery, doubt, awe, and silence. Maybe faith is not certainty, but fidelity to the search itself, the courage to keep turning toward what cannot be proven, yet still feels true. No, I’m not renouncing my faith. I’m trying to tell the truth about it. The version of me that once wrote about faith being universal wasn’t wrong; she was faithful to what she knew then. And the version of me now is faithful to what I don’t yet know. Faith evolves not away from God, but toward a deeper humility before Him. The fracture, the fear, the doubt, they don’t cancel belief; they humanize it, soften it, make it real.

I haven’t stopped trying to make sense of my faith but these days, I think it’s enough that it exists, trembling, uneven, but alive. Faith, for me, is no longer the voice that declares “I know.” It’s the quieter one that admits “I don’t, but I still care.” Maybe that’s all belief has ever been, the willingness to look into the vastness, to see nothing certain staring back, and to whisper, “Still, I believe.”

“Yet, I also know it’s not enough. Belief alone doesn’t quiet the questions !”