I Know It Looks Wrong But I Can’t Explain Why!

For nine months, I lived with a problem I couldn’t name.

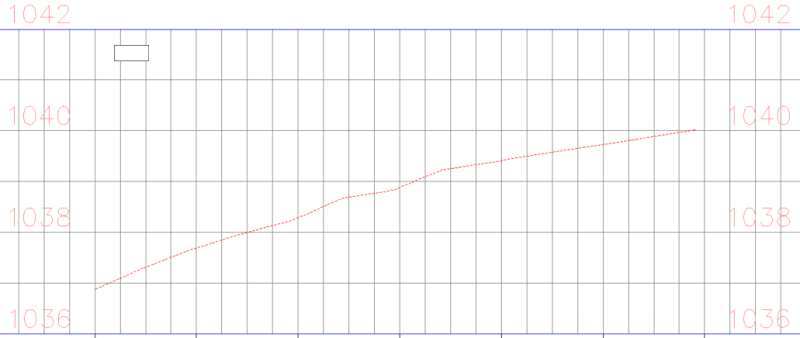

On paper, the road was fine. The drawings checked out. The numbers closed. The levels and centre profiles behaved. And I say centre intentionally, for we will come back to this later. Even the digital terrain model agreed, though slightly hinting at trouble, but offering no explanations. The machine control on the grader was doing exactly what it been told to do, faithfully following the model, obedient to the math. And yet, standing on site, walking the edge of the pavement, something refused to sit right.

There was a kink. Not dramatic. Not catastrophic. Just subtle enough to make the eye hesitate every time you walked the edge of the pavement. The kind of irregularity that doesn’t trigger alarms but quietly unsettles you once you’ve noticed it. The kind that makes you pause, even when every system tells you everything is correct.

As a surveyor, I’ve learnt to trust that pause. If something looks wrong or feels wrong, even when I can’t explain it, I don’t act. I stop. I wait. I question. That instinct has kept me out of trouble more times than I can count, especially in environments where acting too quickly can lock decisions into concrete and asphalt. But this time, that instinct wasn’t enough. It told me something was off, but it couldn’t tell me why, and I couldn’t figure it out either.

The uncomfortable part was that nothing was obviously broken. The DTM was’t wrong, the machine control wasn’t misbehaving. The grader wasn’t doing anything strange. The profile and cross slope, all still balanced mathematically.

Everything was internally consistent, and that made the problem harder to challenge. When systems agree with each oter, doubt starts to feel personal.

Slowly, I had to admit that this wasn’t a construction problem and it wasn’t a survey problem. Maybe it was my problem. I could see the issue. I could feel it in the road. But I didn’t yet have the language to explain it,

….and in engineering, as in any other discipline, instinct without justification has it’s limits. It may stop you from doing harm, but it cannot, on it’s own, defend a concern in a meeting, reshape a drawing, or influence the direction of design.

Somewhere during my undergrad, one of my lecturers once said, “You need to learn how to learn, and you learn by asking questions.” At the time, and for a few years to follow, it sounded abstract, almost philosophical and pretty great philosophy at that. I thought learning meant collecting answers, mastering formulas, standards, procedures, workflows, and whatever needed to be known. Standing on that same stretch of road week after week, watching the machine do exactly what the model asked of it while my instinct disagreed, I finally understood what he meant.

Learning isn’t about answers. It’s about asking the relevant questions.

I had been asking the safe ones. The familiar ones. Was the setting out correct? Were the levels right? Was the road seamlessly tying into its surroundings? Was the model built properly? All valid questions, but none of them reached the heart of the issue. The question I hadn’t asked was more fundamental and far less comfortable: what is the road actually doing in three dimensions paarticularly in the spaces between station points, where the model fills in the gaps and so much of the surface is simply interpolated. I began to wonder whether the same issue would have emerged using traditional methods, or whether this was a risk introduced by building every point of the surface instead of thinking in stations, the paradox of modern technologies.

Once I allowed myself to ask that, the problem began to unravel quietly. I stopped focusing only on the centreline and edges and started paying attention to the in-between, where water flows, and everything geometry tries to hide is exposed. And that is when it clicked, that when vertical curves overlap with superelevation transitions, the edge regions do not behave like the centre regions, not because anything is wrong, but because it is no longer being directly designed. Their shape will follow whatever the geometry tells it to do, and sometimes the layering of the road and relative grads can create regions of “confusion”.

In a model-driven world, the centre is controlled by explicit geometry, while the edges are often derived, interpolated and quietly smoothed by the surface in between. The DTM does what it is built to do: it connects station points, blends sections, and creates continuity where none was explicitly specified. The math balances, the model behaves, and the machine follows, yet the road edge becomes the sum of multiple decisions layered on top of one another. Resultantly, what looks continuous on screen can still feel wrong on the ground. As that same undergrad lecturer used to say;

…these technologies are not perfect and no model is smarter than it’s inputs and that’s where the value of the surveyor lies. In recognizing when the data looks right on the screen but wrong on the ground, and stopping the error there.

There was no single moment of revelation, only a calm relief as the pieces fell into place. The kink wasn’t random. It wasn’t poor workmanship. It wasn’t a survey error. It was an inevitable outcome of geometry that hadn’t been questioned deeply enough at the right moment. And that’s when another truth surfaced, one that was harder to sit with: my inability to articulate that instinct revealed a gap I needed to address. Instinct matters, and I will always trust it. If something feels and looks wrong, I won’t act just because the model says it’s fine.

But instinct alone isn’t enough. Explanation is how concern becomes clarity. It’s how hesitation becomes contribution. It’s how experience grows into design thinking.

This experience didn’t just teach me about geometric confusion, models, or machine control. It taught me that in a world of smart models and obedient machines, human responsibility hasn’t disappeared. It has shifted.

As engineering surveyors, our role is no longer just to make the math work or confirm that coordinates are correct. It is to ask whether that correctness survives contact with the real world. These are ideas we often discuss in conference rooms and technical sessions, but living through it on-site was different. Watching the model and the machine agree with the design while the road told another story gave me an understanding that no presentation ever could.

Nine months later, the kink finally made sense. And in understanding it, I learned something far more valuable than a formula or a workflow. I learned how to ask better questions.